Thru-Hike Success Starts in Your Mind: How to Mentally Prepare for a Long-Distance Hike

A Preface to Heading North

Before my first thru-hike(AT ’18) I was living abroad teaching Math and Science at a pseudo-international school in Yangju, South Korea. I say pseudo because although the kids that graduated the program did receive a US highschool diploma, it wasn’t an international baccalaureate certified school. This was a detail that would become relevant my last year there when similar schools throughout the region started to get busted for having foreigners working on the wrong type of visa, resulting in said waygooks(Korean for “foreigner”) getting deported and subsequent schools closed down. It was also during Trump’s first term where it apparently became cool to try and call the bluff of the Nuclear Man to the north of us. Being shown a nuclear blast radius of something hitting Seoul and how it would impact us residing outside of the city limits was probably one of the least fun times I’ve ever had in my life. Not enough threat to completely annihilate us but enough to have lingering nuclear effects. I vividly remember being in Itaewon at a coffee shop and everything getting silent at 2pm because that was the time the little man’s bomb threat was to become a reality, when we weren’t dead I continued reading and took another sip from my iced-americano. I knew at this point I was ready to pack up all of my belongings into my allotted 2 checked bags and head to whatever was next.

The teaching gig paid well, which enabled me to pay off student loans and have a little extra saved afterwards. And I got 3-4 months of vacation per year with which I would use to go on extended trips across the globe like a couple of weeks in Vietnam – where I bought a flight into the country and a flight out of the country 2 weeks later with no itinerary in between other than get from Ho Chi Minh to Hanoi so I could catch my flight out. There were tons of smaller trips like summiting Mt. Fuji, bicycling across South Korea, and hiking about 12 miles of the Great Wall. After getting the “adventure travel” bug, I’d decided I wanted my life to more enriched with something they couldn’t take away – the lived experience. When my contract in Korea came to an end the choices became pretty clear – either I was going to move to Berlin and start a business(I had a great time while visiting a friend from high school) or I was going to hike the Appalachian Trail. After my grandfather’s health started to decline I decided a 4 hour flight home to Texas from the East Coast was more practical than a 14 hour one from Germany. This would prove to be the right decision as he would succumb to pneumonia the next year and would never get to see me marry the woman I met outside of Fontana Dam on that very same AT thru-hike.

Chapter 1. On Isolation

A couple of skills that I acquired during my time in Korea and my experiences solo traveling came in handy while thru-hiking. One was an ability to deal with isolation and not be afraid of being on my own for extended periods of time. It’s important to note that I’m not purely talking about physical isolation, but of a mental one. If you’ve got a big family or friend group and haven’t really had those support systems stripped, be prepared to be your own rock when a bear steals your food bag, your inflatable pad gets a slow leak, and you find out during a flash storm that you didn’t pick the most ideal spot and are now soaked.

Although you’re going to inevitably meet other hiker hopefuls, being prepared mentally for some extensive alone time is very helpful. I used to romanticize being the log-cabin loner left to my own devices and maybe having a dog or two to keep me company while I whittled away and pontificated on what it really meant to be human a la Dick Proenneke. But, ultimately, I’ve learned I’m pretty social, and the nail in the coffin was watching a documentary on a man and woman living in a remote part of Alaska where the man, Heimo Korth, stated if his wife died he’d move into town. That humans weren’t meant to be alone. This is an ideological view I currently subscribe to and would be willing to bet many of you reading this might find out the hard way that you subscribe to as well.

Accordingly, I would encourage anyone who’s setting off to thru-hike to be alone in the wilderness to either A. mentally prepare for what that actually means, to really be alone or B. mentally prepare for that not being granted. If you’re really that type of isolationist that thrives on being alone, you should conversely prepare for the reality of not being granted that solo time. The reality of public spaces, camp sites, etc being well occupied.

This isn’t supposed to be a fear monger section and in truth my experience was making my first friend before I even got to trail, a dude by the name of Brandon and I met on the Greyhound bus leaving Atlanta headed the direction of Springer Mountain. He had a big backpack and was wearing Darn Tough socks so I assumed he was traveling to Maine, and I was right. From that point on the only real solo hiking time I had was a stint in which I had returned from a weeklong visit home for my grandfather’s 80th birthday and had to catch up to my now girlfriend “Honeybear!” whom I met about a month into the experience right at the start of trekking through the Smokies in late April. So, maybe you’re alone, maybe you’re not.

Regardless of your reality you need to be prepared for what might be. The AT is famous for being the first real overnight trip many people have ever taken, my story wasn’t much different save for a couple of shakedown camps with friends while I tested out my gear. If you’re planning on something like the CDT or PCT for a first thru-hike, you’re more likely to have that alone time if that’s what you’re looking for.

How to deal with the isolation

It might seem pretty obvious but a good way to prep for this isolation is to go on solo overnighter trips and get used to all the noises and potential shadowy figures lurking in your mind. The hardest part of an isolated experience is really the morale and support you get when times are tough. If you find yourself having a tough time, talking it out with anyone you can is helpful. Preparing friends or family back home about how to deal with you when you think you want to quit is useful. Letting them know why you’re hiking that has more depth than “because it’ll get me laid when I talk about it at parties afterwards” is paramount. And p.s. most people in normal life will not be able to comprehend what hiking for 6 months means when you tell upon your return – their eyes glaze over and their body starts to levitate as they disconnect from whatever willfully vagrant summer you partook in while they wonder why you weren’t contributing to your 401k and driving a car like every other red blooded American. More existential meanings like “I’ve always wanted a grander adventure” “I want to prove to myself I can finish what I start” “I want time to think about my purpose outside of vocation and societal duties” etc are all why’s that you can carry for thousands of miles that will remain as true on the day you leave for trail as the day you finish it.

You’re going to be away from the people you love for 4-6+ months living in the dirt, dealing with snakes, hot, cold, rain, snow, and worst of all – mosquitos and biting flies. There comes a time in every hiker’s life when they’ve shit their pants and a chaffed ass will have them wondering “what the fuck am I doing here”. Some helpful tips for dealing with this while on trail are: journaling your thoughts – not only is this great for your mental set it’s nice having something you can look back on when you’re finished, setting small goals for each day, practicing mindfulness, or even carrying small rituals like a favorite song, a sketchbook, or a book. For me personally, I was bored on the Appalachian Trail a lot of the time, some of it was the green tunnel, but it was also not having a creative outlet. Some might think it’s lame to document your hike in video form, photo, blogging, vlogging, etc, but on my second thru-hike, the PCT in ’21, I vlogged and taught myself how to edit videos on my phone and now I do all of the photo, video, and creative stuff here at ULA. So, if you’re a creative person, having a creative outlet while on a thru-hike might enrich your experience and help generate a better context of your hike while you’re on it. The mental attitude I had on the PCT vs the AT was a night and day difference and I don’t think it was just that the PCT is better than the AT in every way.

Chapter 2: On Resiliency

Another skillset I learned while living and traveling abroad was the resiliency to change plans and adapt to new demands as they came into play. Sitting on a 7 hour bus ride from Kathmandu to Besishahar where my legs are cramped and my seat gets stolen after a bathroom break pissing on a wall? Great! Sleeping on the floor of the Kuala Lumpur airport on an overnight layover after my connecting flight gets canceled? Fuck yeah! Not sleeping during an overnight ride on a Chinese train because the patrons are smoking INSIDE of the train and the family in my bunkhouse is listening to their phone on full volume without headphones? Please sir, could you rotate your screen so I can watch this reality show in Mandarin with you? While you’re on a thru-hike nothing is really guaranteed. The weather can change in an instant, the hostel might not have room, and some asshole ahead of you might have bought the last burger at the convenience store grill you’d been thinking about for the past 3 days. These little inconveniences can really destroy your morale.

Another large component of resiliency is pretty obvious: the physical demands of the trail. Long days of walking put your body under constant stress, from sore muscles and aching joints to blisters and fatigue that just won’t quit. Even minor injuries like cuts, sprains, or strains can become significant obstacles if not addressed carefully, and maintaining proper nutrition and hydration adds another layer of challenge.

Developing physical resilience before the trail begins can make these daily demands feel more manageable and keep you moving mile after mile. The best way to get prepared for backpacking is by backpacking. Doing fully loaded pack hikes as a means for preparation will give you an understanding of how your pack will feel on hour 5 out of 12. Also known as the latest in fitness trends “rucking”. Ruck Yeah!

As mentioned in chapter 1 mental and emotional resilience is just as critical. Thru-hiking often means long stretches of solitude, which can stir feelings of loneliness, anxiety, or boredom.

Resilience also shows up in social interactions. Sharing trail space with other hikers brings opportunities for connection, but it can also bring conflict or tension. Although I am mostly sociable, I am also a youthful curmudgeon whose meter gets full fairly quickly. Everyone hikes at their own pace, and learning to navigate differences in personality or speed without letting frustration take over is an important skill. Alternatively, as a dude, being in an environment like a thru-hike around women will quickly learn you a thing or two about what you thought was appropriate and what is actually not appropriate. More on that here. Trail life requires patience, empathy, and the ability to adjust to the social dynamics of a constantly changing group of people. Don’t even get me started on what I deemed “shelter hopping” or the constant and incestuous aspect of everyone hooking up with each other. I thought Sprocket was hiking with Horseshoe but it turns out they broke up, now he’s hiking with Flim Flam and Flim Flam’s old flame Toilet Water left trail with Big Sneeze to be in a throuple with them and Don’t Quit. It’s can be a lot of drama!

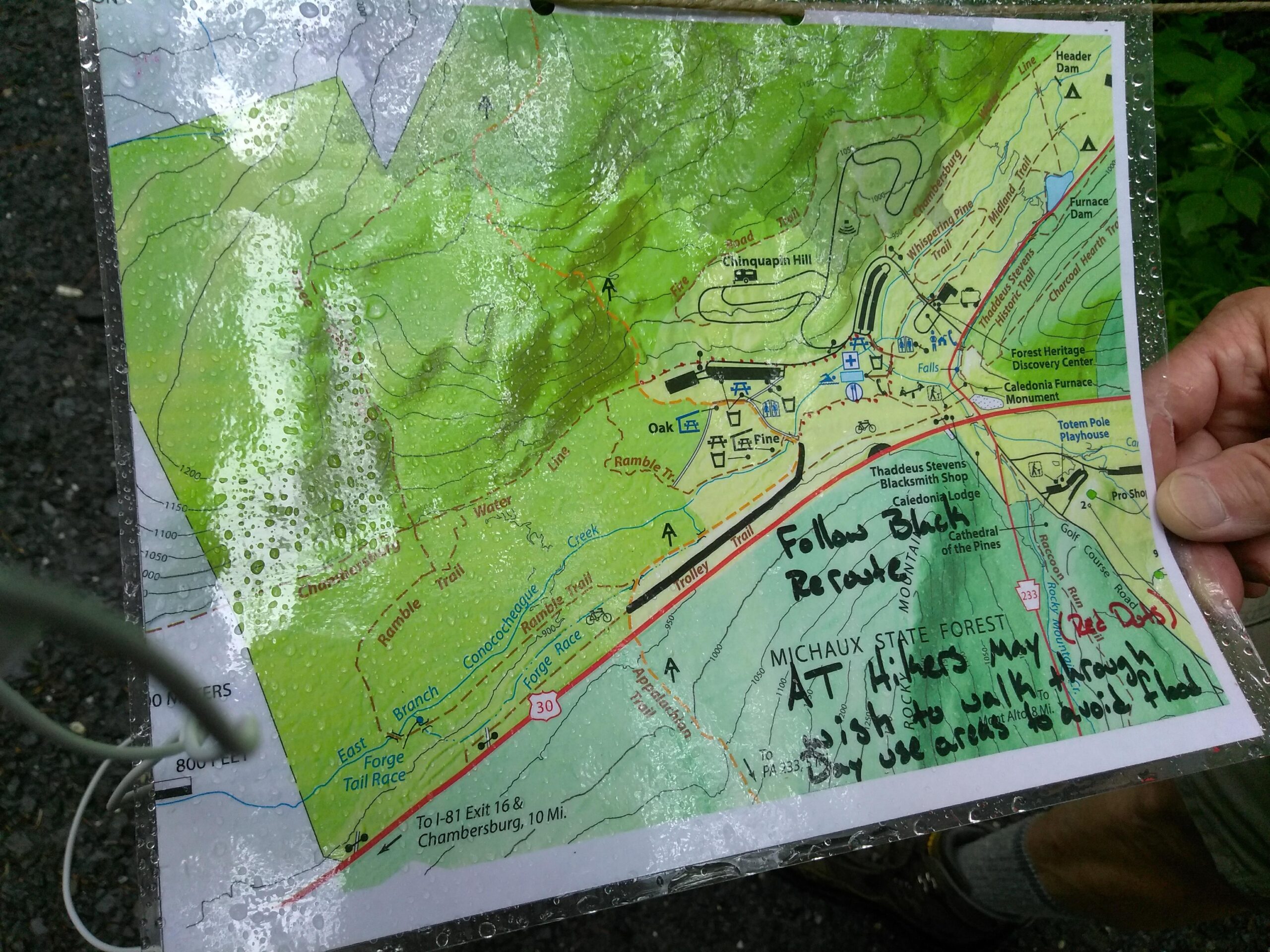

Finally, resilience is tested in decision-making. You have to know when to take a zero day to recover and when to push forward despite discomfort. As “Just Joe” told us – sometimes it’s just new pain. Unexpected challenges like gear failures, navigation issues, or trail closures require quick thinking and adaptability. On our PCT hike, fire closures and the prospect of not having clear views of Rainier in the Goat Rocks Wilderness section were scary. Every choice has consequences, and learning to make thoughtful decisions under stress is a crucial aspect of thru-hiking.

The old adage that remains true is this: if you think you want to quit trail, just take a day off. If you still want to quit, take another day off. And if you still want to quit after that, just make it to the next town and see how you feel. Finally, if after all that, you still want to quit, just don’t. The only difference between the ones that make it to the end and the ones that don’t is a stubbornness to not quit even when you want to. A thru-hike is one of the most binary experiences there is in life. Either you finish or you don’t. When my IT band was messed up because I pushed too many miles too fast I listened to the dude at Outdoor 76 in Franklin who took us to church about going into physical debt and doing more than your body was ready for. The people in my tramily who were suffering similar ailments and scoffed at the lecture and decided to wait outside instead ended up getting off of trail to do “something more fun”. But when it comes to physical demands, you need to be mentally ready to take a day off in town and let your tramily you’d built go on without you. The only acceptable reasons to leave trail in my opinion are as follows: unavoidable personal injury or a family emergency. I’d never encourage someone to stay on trail over becoming a care taker for a relative etc.

Chapter 3: On Pre-existing Emotional or Mental Trauma

This might be counter to the narrative that some people hold and don’t forget this is a personal opinion of one guy. But, thru-hiking is not a mental health fix. I’ve heard of and seen first hand people going off their meds while on a thru-hike and it only ever ended up being a bad time for not only the person who stopped taking their medicine but also the people around them. None of this is meant to take away from those that really did find themselves and a sense of peace while out on a thru-hike.

This is the perspective of someone finding out just how messed up they were while enduring the green tunnel with nothing else to distract them. If you’ve got any type of unresolved trauma in your life it’s going to show up while you’re out on a thru-hike. There are some demons that will follow you into the woods and pre-existing mental illness, trauma, and the like are Legion. This is more for the younger people who are experiencing and learning about this side of themselves for the first time. If you’ve experienced ruminating or racing thoughts without a clear way to cope, if you’re prone to substance abuse, or suffer from overarching anxiety and depression, a thru-hike is not likely to relieve you of these ailments and in many cases will exacerbate your problems.

The more self-aware you are off-trail, the better you can manage your emotions on-trail. Without getting too personal in a blog about backpacking, for me it was childhood trauma that I had not unpacked and came to the forefront during the green tunnel of the Appalachian Trail. The baggage I carried in my personal life had snuck its way into my backpack and I was now carrying it with me through Virginia. It’s a side of things that I don’t see put forward enough so I’m doing it here.

Everyone loves to talk about how transformative the experience was or how much fun they had and all of that, but it can get very dark as well. So preparing yourself as best you can for those things coming into play is going to go a long way. And again, not everyone will share this perspective or have this experience.

Pay attention to your moods, stress levels, and triggers. Journaling, meditation, or even brief reflection during breaks on trail can help you recognize patterns before they spiral. If you’re already seeing a therapist it’s probably a good idea to talk with them about your plan to thru-hike and what kind of coping mechanisms you can arm yourself with if you’re not in need of medication. Some go-to coping for high stress is breathing exercises, meditation, a stretching routine, journaling, and a creative outlet.

Chapter 4: On Visualizing the Journey

One of the most powerful tools for mental preparation is visualization. The trail can be unpredictable, and the miles ahead may feel overwhelming, especially for a first-time thru-hiker. Taking time before you even step on the trail to imagine the journey helps train your mind to navigate both the challenges and the rewards you’ll encounter. Now let’s get woo-woo and new agey.

Start by picturing the start of your hike: Imagine the early miles, new experiences, making new friends, and really doing it. Then picture the harder moments like a steep climb, a sudden rainstorm, or an unexpected obstacle that tests your patience. See yourself handling it calmly, adjusting your pace, and finding solutions rather than frustration.

Visualizing doesn’t just prepare you for difficulty; it helps you savor the beauty of the experience. Picture reaching an incredible camp spot after a long day, the satisfaction of setting up camp and getting into your tent. These mental snapshots create anticipation and motivation for the journey ahead, making the trail feel more familiar before you even begin.

You can also use visualization as a rehearsal for decision-making. Imagine scenarios where you might need to change plans: adjusting for weather, choosing to take a zero day, or navigating a challenging section of trail. Mentally practicing these situations builds confidence and reduces anxiety when you face them in reality.

The key is consistency. Even a few minutes of visualization each day in the weeks leading up to your hike strengthens your mental endurance. By training your mind to expect both the highs and the lows, you step onto the trail with a sense of preparedness and calm. Visualization turns uncertainty into familiarity, and challenges into opportunities to see what you’re capable of. The strongest visualization will be the one of you completing the journey, but don’t forget that it’s a series of steps.

Visualizing is a great tool but it’s also important to remember that while you’re on trail to try and take it day by day, thinking about the entire 6 month journey on day one can feel overwhelming. I will never forget feeling claustrophobic on the first night of my hike. It felt like my quilt and tent were suffocating me and I didn’t know how I was going to pull the whole thing off. I finally got to sleep and the next day I talked it out with Brandon who said he’d felt similarly as we headed North. It’s normal to feel overwhelmed when you start your first thru-hike. Be prepared for this feeling.

Recap:

Prepare for an isolated experience.

Thru-hiking is inherently a solitary endeavor, even if you’re surrounded by a trail community at times. You’re the only one that’s going to decide to go all the way. You will have good friends leave trail and quit. There might be long stretches where you are alone with your thoughts, miles away from the nearest town, and hours from anyone who knows your name. Mental preparation means practicing solitude before your hike — whether that’s taking solo overnight trips, long walks without distractions, or quiet hours outside without your phone. Learning to be comfortable in your own company and finding ways to stay grounded during these moments will make the trail feel less daunting and more like an opportunity for self-reflection and growth.

Prepare to be resilient when things don’t go how you want them to.

The trail is unpredictable. Weather changes, sore muscles, gear failures, or unexpected trail conditions can all disrupt your plans. Resilience is about adapting, accepting setbacks, and finding solutions without letting frustration derail your experience. Developing this mental toughness before your hike by pushing yourself through challenges off-trail or practicing problem-solving in stressful situations makes the inevitable obstacles on the trail feel manageable instead of overwhelming. The more you cultivate resilience, the more confident you’ll feel when the trail tests your limits.

Prepare to face any existing trauma head-on.

Thru-hiking isn’t just a physical journey; it can stir up emotional challenges that have been buried or unaddressed. Long stretches of solitude, combined with the mental and physical demands of the trail, can bring unresolved emotions to the surface. Mental preparation includes being aware of your triggers and having strategies to cope whether that’s journaling, mindfulness, therapy, or talking with trusted friends. Confronting these experiences on the trail can be difficult, but it can also be transformative, providing clarity and healing that’s hard to achieve anywhere else.

Know why you’re hiking and talk to friends and family about your reasons.

Your “why” is the anchor that keeps you moving when motivation fades. Understanding your purpose, whether it’s personal growth, adventure, challenge, or clarity, gives meaning to each mile. Sharing this with friends and family creates a support system off-trail; when you feel doubt, fatigue, or loneliness creeping in, they can remind you of the reasons you started. Having these conversations ahead of time ensures that your why stays visible and accessible, even when you feel mentally or physically depleted.

Visualize your hike.

Visualization helps make the unknown more familiar. Studying maps, planning resupplies, or using apps like FarOut to break your hike into manageable sections gives your mind a framework to navigate the journey. Imagine each section: the climbs, the valleys, the campsites, and the town stops. Mentally rehearsing scenarios, from difficult terrain to resupply days, prepares you for both challenges and rewards. Visualization trains your mind to expect highs and lows, turning uncertainty into confidence and making each mile feel like a step toward a known, achievable goal.

0 Comments